“Opening up the national debate is already a triumph”: a lowdown on the LUC referendum in Uruguay

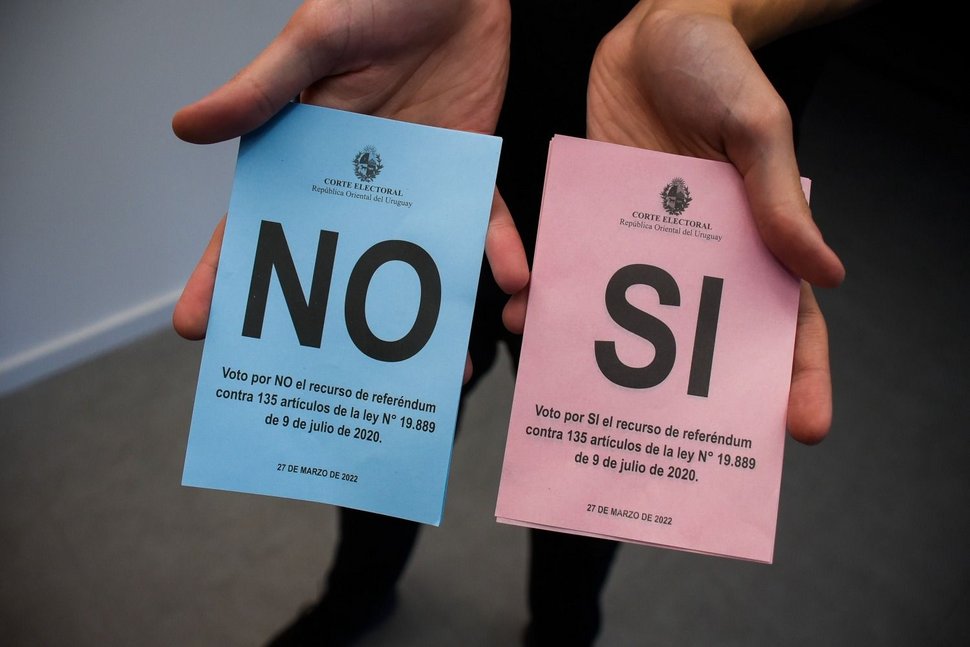

Any comprehensive assessment of Uruguay’s March 27 referendum – where citizens got the final say over whether to repeal 135 articles of a new flagship law being pushed by the government – should look beyond the turnout and the ‘yes vs no’ voting split.

Rather, it should also consider the symbolic social (and political) mobilization that brought it about in the first place – putting citizens front and center of a debate impacting situations of competing rights: the right to protest in the streets and the freedom of movement, the right to strike and the right to go to work.

CIVICUS describes Uruguayan civic space as “open”. Indeed, the country is something of a green outlier nestled in a continent increasingly beset by social conflict and curbs on civil society (as documented in this DL report).

And yet there it is. Uruguay. A nation that, for better or worse, resisted lengthy lockdowns during the worst of the pandemic and where, in contrast to its Latin American neighbors, confidence in democratic institutions grew in 2021, according to data from Latinobarómetro. But how does this democratic health relate to the vote, and why, beyond its outcome, does the fact that the referendum was held in the first place speak so well of Uruguayan civil society influence? We attempt to explore these questions here.

The mother of all laws

The Law of Urgent Consideration – or simply LUC – presented by the government 40 days after Lacalle Pou came to power, is a broad-spectrum law encompassing much of the president’s government plan.

It is split into 476 articles covering diverse topics – from public security, education, public enterprises and the economy; to finance, agriculture, social security and labor relations; through to social development, health and emergency housing.

It entered Parliament with a request for urgent debate. In procedural terms, this meant the legislative chambers had to analyze it, convene public hearings, propose amendments and vote on it within pre-established and extremely tight deadlines: 45 days in the chamber of origin (the Senate) and 30 in the reviewing chamber (the House of Representatives). It is important to note that bills for urgent consideration may only be submitted by the Executive branch, and that if they are not voted on as stipulated, they are automatically approved with their original text.

A unique case? Yes and no. Since the return to democracy in 1985, 13 bills for urgent consideration have been submitted to the legislature, nine of which approved and four rejected. However, most of them were not nearly as broad in scope as the present Law.

Civic freedoms

The passing of the LUC through the legislature and its subsequent enactment came amid numerous, extensive debates as well as demands and campaigns from different quarters. Here, we look specifically at features of the Law posing potential risks to civic space – in particular the right of assembly, protest and access to public information. We focus on the following six aspects of the Law (for an overview of all the Law’s articles click here):

- 1. The introduction of a crime of ‘police aggravation’, in the form of obstructing, attacking, throwing objects, or threatening and insulting police officers. This carries punishments of 3 to 18 months imprisonment, with participation of more than three individuals being an aggravating factor (article 11).

- 2. The modification of the principle of legitimate self-defense in Article 26 of the Penal Code, by which persons acting in defense of themselves, others or property are exempt from liability when the “means used are sufficient and adequate to avert the danger”, and regardless of whether they have been physically assaulted (Article 1).

- 3. The banning of picketing when it impedes the free movement of persons, goods or services in public spaces or in private spaces for public use (article 468), and when it impedes the right to freedom of work and the running of a private company guaranteed by the State in the event of union actions that obstruct the entrance to facilities (article 392).

- 4. Go-ahead for police actions based on “criminal appearance” (article 470).

- 5. The duty to identify oneself, which applies to all persons when the Police so require and the right of the latter to take them to police premises in the event of failing to produce identification (Article 50).

- 6. The confidentiality of all information and records that make up the National Intelligence System of the State and its personnel regardless of their position (Article 125).

Legislative debate and civil society input

The bill entered the Senate on April 23, 2020. For its debate, special committees were formed in which representatives of unions, professional entities, universities, civil society organizations and business chambers were present and gave their views. Among them were the Universidad de la República, Universidad Tecnológica and Universidad de Montevideo; civil society organizations and networks such as Nada Crece a la Sombra, El Paso, ASFADIVE, EDUY21, Mujer Ahora, Servicio de Justicia y Paz (SERPAJ), Centro de Archivos y Acceso a la Información Pública (CAINFO), Asociación Nacional de ONG, Red Uruguaya de ONGs Ambientalistas; federations of teachers and university students.

It was in this chamber where most of the modifications were introduced, although the House of Representatives also made some revisions. In the end, thanks to the legislative majority of the five-party government coalition, the law was approved in under 100 days by 18 votes in favor (out of 30) in the Senate and 57 out of 98 in the House of Representatives. In the process, the bill lost 25 of its original articles and had modifications made to 300 others.

A mechanism of direct democracy

Uruguay boasts the most developed and applied direct democracy mechanisms in the region. Holding referendums for citizens to be able to challenge laws that have been passed by Parliament, albeit within a maximum period of one year following their enactment. is among those mechanisms guaranteed by its Constitution.

There are two ways for filing a referendum appeal against a law before the Electoral Court: a “short” and a “long” one. The former consists of gathering the signatures of at least 2% of the total number of registered voters (around 50,000) within 150 days of the law’s enactment, which if achieved triggers a ‘pre-referendum’ where voting is voluntary. Only if 25% of the electorate votes yes then the referendum takes place, and this time the voting is compulsory. The longer process, meanwhile, requires the signatures of 25% of the electorate (about 700,000 people) within one year of the enactment of the law, which if obtained leads directly to a full referendum.

In this particular case, each option posed challenges, especially in the context of the pandemic. The short process described above, while easier to instigate, does not, by virtue of relying on voluntary voting, guarantee that enough people turn up on the day to cast their ballot (previous efforts to overturn laws in this way have been scuppered by low turnout). However, the alternative of summoning the signatories necessary to trigger a compulsory referendum outright is itself hugely challenging given the numbers required and timelines. There was certainly much debate over which of the two mechanisms to opt for. Eventually the longer, more direct route was chosen. Though even within the Frente Amplio bloc, there were disagreements on the matter.

The path to a referendum

Even before the approval of the LUC, social movements and civil society organizations made their objections felt through demonstrations and strikes. But how did this ultimately lead to civil society, and the citizenry at large, joining ranks to take control of the debate? And to what extent did the aforementioned institutional mechanisms guaranteeing citizens the right to challenge enacted laws, and the wider political culture, play a role?

When all is told, this is a story about how, by casting aside their differences, over a 100 social and political organizations, large and small, joined together in a bid to have a final say over the new Law: first by creating the National Pro-Referendum Commission, then by agreeing on which referendum mechanism to pursue, after that by deciding on the articles of the Law to be submitted to a public vote, and then, finally, by presenting their request to the country’s Electoral Court.

The highest profile figures offering their support to this campaign were the national workers’ group PIT-CNT (headed by its president Fernando Pereira, who later became president of the opposition party Frente Amplio), the Uruguayan Federation of Housing Cooperatives for Mutual Aid (FUCVAM in Spanish), the Federation of University Students of Uruguay (FEUU in Spanish) and Intersocial feminista – an umbrella for some 20 feminist collectives and other smaller groups. On the other hand, there was Frente Amplio. Although it was the Intersocial that initially promoted the referendum, there were parallel debates within each of these sides to bring positions closer and articulate their decisions.

Race to collect signatures

Just over 670,000 signatures were needed to trigger the referendum. Nearly 800,000 were obtained – unprecedented in the history of public consultations of this kind. Yet getting there was not easy.

To begin with, the collection campaign began in January 2021 and the deadline for submission was July (one year after the enactment of the law). Barely six months, then to gather the needed signatures, and amid a worsening of the pandemic especially between April and May. In view of the government’s refusal to consider an extension of the constitutional deadline, the campaign rolled on despite the various challenges.

The last weeks were the most critical. Four days before the deadline, they were 40,000 signatures short. Things were looking bleak. Yet they would go on to amass another 165,000 endorsements. How? By launching a powerful, united and well coordinated call to action mobilizing hundreds and hundreds across the country’s neighborhoods, even spilling over into other countries. This prompted a late surge in support and, on July 8, the National Commission duly presented a total of 797,261 signatures to the Electoral Court.

Campaigns for ‘Yes and No’

The “Campaign for the Yes” (those in favor of repealing the articles) was launched at the end of October 2021 at an event in Montevideo with the participation of the PIT-CNT, several social organizations, and political figures of Frente Amplio (including former president José “Pepe” Mujica and the mayors of Canelones and Montevideo, Yamandú Orsi and Carolina Cosse). The National Pro-Referendum Commission was renamed “National Commission for the Yes” and the slogan “The LUC is not Uruguay” took shape. The campaign’s closing ceremony was on March 22, with the transmission on national TV of a message delivered through the faces and voices of a group of people appealing for a ‘yes’ and for political preferences to be cast aside.

Although the various organizations behind the “Yes” campaign worked concertedly to woo the public, each also mobilized its own agenda and, accordingly, focused on particular aspects of the Law. Thus, the trade union organizations led discussions on the articles impacting labor relations; the feminist groups, on the effects for women and minorities in vulnerable contexts; the teachers’ and students’ organizations, on articles linked to education; the human rights organizations, on reforms to the criminal procedure codes, and so on. In addition, they made formal proposals aimed at the openness and social visibility of public decision-making processes, including the duration of the legislative debate and spaces for organizations to voice their views.

The “Campaign for the No” got underway, officially, on January 31, 2022, but already by September 2021 figures from all the parties of the ruling Multicolor Coalition had participated in what was considered the first political act supporting the 135 articles. In November, their first promotional videos began to circulate under the slogan “Defend your freedom“, which would later become a staple of the campaign. The wind-down came on March 23 during a nationally televised press conference attended only by President Luis Lacalle Pou.

What were the “No” campaign’s arguments? That the law reflected popular demands; that it had been debated, modified and approved by a wide margin in Congress; and that since its entry into force in July 2020, it had not had the negative consequences alleged by its detractors, but rather positive ones as predicted by the government, such as halting the rise in crime.

It is worth mentioning that in the lead-up to the referendum, several debates on the Law were shown by public media. The first one was held on February 23, 2022 by senators Oscar Andrade (Frente Amplio) and Guido Manini Ríos (Cabildo Abierto) and focused on security, education, housing and labor relations. On March 7, senators Mario Bergara (Frente Amplio) and Gustavo Penadés (Partido Nacional) presented arguments for and against the articles on education, security, housing and financial freedom.

There were several others, including a series of discussions on Law’s impact on the economy, housing and education organized by Universidad Nacional de la República with the support of TV Ciudad on March 21 and 22.

Half and half

Of the total of 2,215,906 valid votes cast, the No vote obtained 1,108,360 (50%) and the Yes vote 1,078,425 (48.7%) and there were 29,121 blank votes that counted as No’s. (In addition, there were over 82,000 annulled votes, something which in itself merits discussion). As a consequence, therefore, the 135 articles of the government’s controversial Law are to remain in force.

Considered at the departmental level, the Yes campaign obtained its best results in Montevideo (53.4% vs. 40.8%), Paysandú (48.0% vs. 44.4%) and Canelones (50.7% vs. 43.1%), and the worst in Artigas (30.3% vs. 62.8%) and Rivera (24.1% vs. 69.7%). This marks a pronounced cleavage between the capital and the interior of the country.

This election has been interpreted by many media outlets as a de facto referendum on Lacalle Pou’s administration, which currently has an approval rating of just over 50% (see this DL report), and a stress test for the Multicolor coalition following internal tensions. The fact that the president was the only visible face at the ‘No’ campaign closing event certainly opens the door to these interpretations while showing how important the result was for the government.

However, the unprecedented collection of 800,000 signatures, the high voter turnout of 85% and the small margin that settled the election – much tighter than that predicted by polls in January and February – is also a sign of how ordinary Uruguayans ended up effectively ‘owning’ the debate, which transcended the legislature and political divides and mobilized the whole of society. This also sets the tone for the important legislative debates to come, among them over media and social security reforms backed by the government.

In the words of the ‘Yes campaign’: “the great problems of the country must be discussed among us all”. The referendum allowed for that – for citizens to, in effect, legislate for themselves.